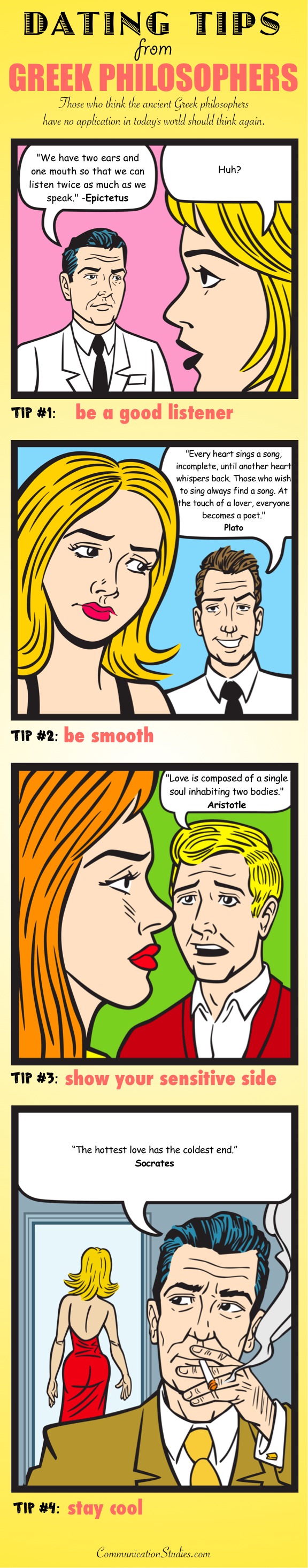

I've been busy getting ready for grad school starting next week. However, I found this and thought people might enjoy it.

Source: Communication Studies

Have a nice day!

|

| This picture is page 1r (screen 11) from Gallica Bibliothèque Numérique |

"Demosthenes sets about proving this by point out that in the course of his speech Aiskhines quoted from Euripides' Phoinix, which he had never performed onstage himself. Yet Aiskhines never quoted from Sophocles' Antigone which he had acted many times. So, 'Oh Aiskhines, are you not a sophist...are you not a logographer...since you hunted up [zētēsas] a verse which you never spoke onstage to use to trick the citizens' (19.250)

The argument that underlies Demosthenes' comment says a good deal about Athenian attitudes toward elite useof literary culture. According to Demosthenes, Aiskhines is a sophist because he "hunts up" quotes for a play with which he had no reason to be familiar in order to strengthen his argument. Clearly the average Athenain would not be in a position to search out quotes when he wanted them; if the ordintary citizen ever wanted toquote poetry, he would rely on verses that he had memorized, and his opportunity to memorize tragic poetry was limited" (Ober & Strauss 251).Although this seems obvious, it had never occurred to me that access to tragic texts might have been limited for much of the Athenian populace. In Book III of the Republic, Plato discusses a number of different passages of poetry. All of them come from the Iliad or the Odyssey and not a single one from tragedy, although the critique here extends explicitly to tragic drama. The choice of those specific passages from the Iliad and the Odyssey is an interesting topic, and one I explore thoroughly in my thesis. However, it had always baffled me that not a single line of the tragic poets appeared in the text. The quotation above illuminates this question.

|

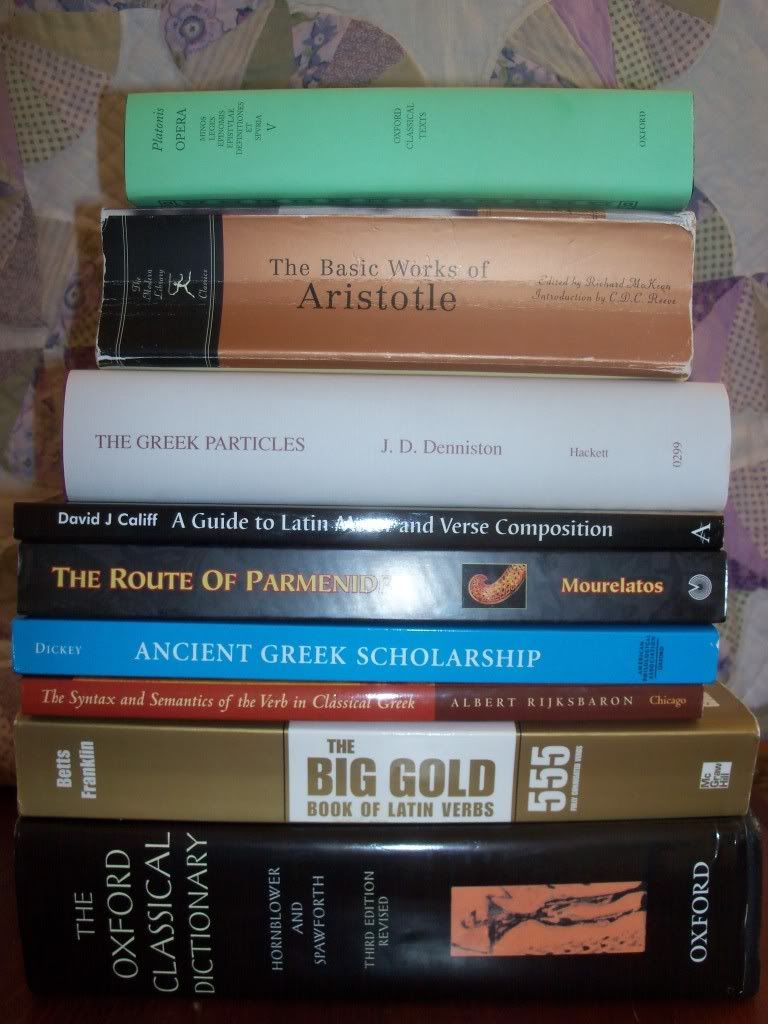

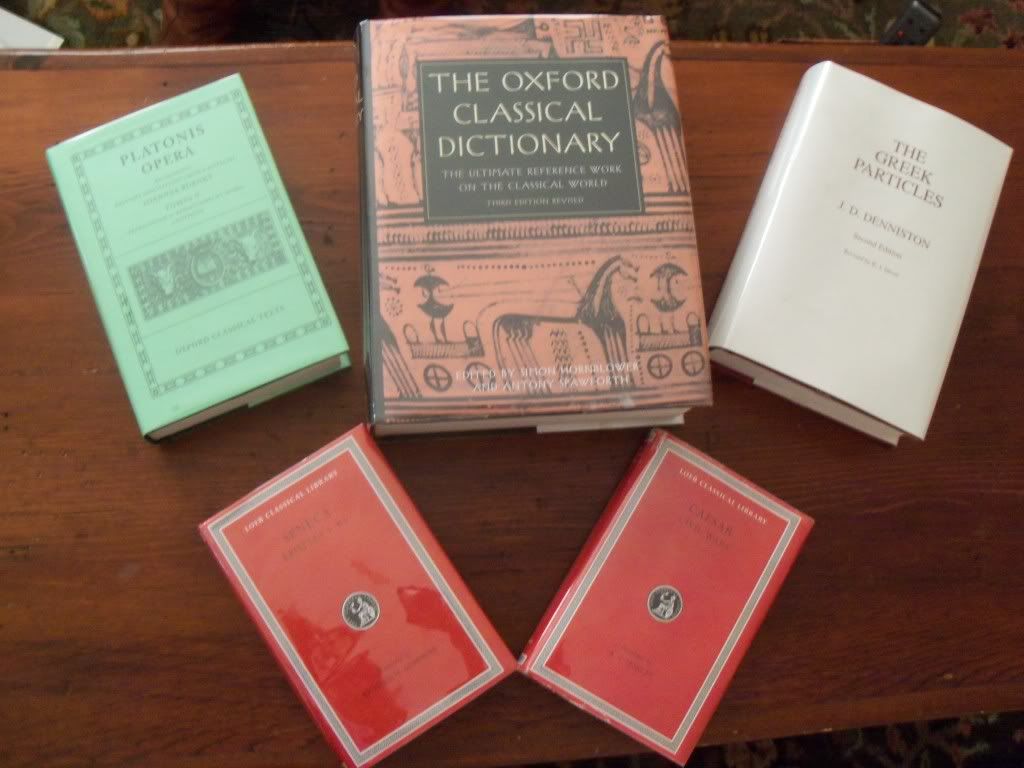

| Birthday Books |

|

| Covered books |

"Alles in allem erweist sich der Phaidros als ein Werk, dessen Teile wie bei einem Organismus (264 c2-5) wohl aufienander abgestimmt sind. Thema ist, unter welchen Bedingungen ein λόσος dem anderen uberlegen ist. Entscheidend hierfur is einmal der bedeutendere Inhalt, was in drei konkurrienden Reden vorgefurt wird. Die siegreiche ist die inhaltich reichste und tiefste: was sie entfaltet, sind die geforderten πλείονος ἄξια oder τιμιώτερα (im Vergleich zu den Reden, die sie unbertreffen will)" (SzlezakI am having a rather difficult time. The German is hard-- at least for me as I am just learning-- but I believe the endeavor is important. Wish me luck!47).

Socrates: Well, then, let us take me, or you, or anything else at hand, and apply the same principle—say Socrates in health and Socrates in illness. Shall we say the one is like the other, or unlike?

Theaetetus: When you say “Socrates in illness” do you mean to compare that Socrates as a whole with Socrates in health as a whole?

Socrates: You understand perfectly; that is just what I mean.

Theaetetus: Unlike, I imagine.

Socrates: And therefore other, inasmuch as unlike?

Theaetetus: Necessarily.

Socrates: And you would say the same of Socrates asleep or in any of the other states we enumerated just now?

Theaetetus: Yes.

Socrates: Then each of those elements which by the law of their nature act upon something else, will, when it gets hold of Socrates in health, find me one object to act upon, and when it gets hold of me in illness, another?

Theaetetus: How can it help it?

Socrates: And so, in the two cases, that active element and I, who am the passive element, shall each produce a different object?

Theaetetus: Of course.

Socrates: So, then, when I am in health and drink wine, it seems pleasant and sweet to me?

Theaetetus: Yes.

Socrates: The reason is, in fact, that according to the principles we accepted a while ago, the active and passive elements produce sweetness and perception, both of which are simultaneously moving from one place to another, and the perception, which comes from the passive element, makes the tongue perceptive, and the sweetness, which comes from the wine and pervades it, passes over and makes the wine both to be and to seem sweet to the tongue that is in health.

Theaetetus: Certainly, such are the principles we accepted a while ago.

Socrates: But when it gets hold of me in illness, in the first place, it really doesn't get hold of the same man, does it? For he to whom it comes is certainly unlike.

Theaetetus: True.

Socrates: Therefore the union of the Socrates who is ill and the draught of wine produces other results: in the tongue the sensation or perception of bitterness, and in the wine—a bitterness which is engendered there and passes over into the other; the wine is made, not bitterness, but bitter, and I am made, not perception, but perceptive.